Main Text

1 Introduction

Mitochondria are organelles that exist in most cells and are enclosed by double membranes, which can produce energy in cells and are the main site for aerobic respiration, known as "power houses" [1]. Mitochondrial transfer refers to the process in which intact, functional mitochondria from donor cells (such as mesenchymal stem cells [2], fibroblasts, etc.) enter adjacent recipient cells through intercellular connections [3]. This process is of great significance to cells. For example, in the repair of tissue damage, mesenchymal stem cells can rescue damaged alveolar epithelial cells or cardiomyocytes through mitochondrial transfer [4], and in immune regulation, mitochondrial transfer can affect the differentiation and function of T cells [5]. In addition, this process also plays a key role in various physiological and pathological processes such as neuroprotection and acute kidney injury [3].

Network pharmacology is a new discipline based on the theory of systems biology, which analyzes the network of biological systems and selects specific signal nodes for multi-target drug molecule design [6]. Network pharmacology emphasizes the multi-pathway regulation of signaling pathways to improve the therapeutic effect of drugs, reduce toxic side effects, increase the success rate of clinical trials for new drugs and save on drug development costs.

Thymocytes, the precursor of T cells, are densely packed in the cortex and account for 85% to 90% of the total number of thymic cortical cells [7]. The viability of T cells, the main cells responsible for cellular immunity, has an important relationship with mitochondria. Thymic epithelial cells are important stromal cells in the thymus, with their protrusions interconnected to form a mesh-like structure, playing a crucial role in the differentiation, development, and selection of thymocytes.

Ginsenoside is a steroid compound, also known as triterpenoid saponin, which is considered an active ingredient in ginseng and has become a highly popular research target [8]. Ginsenosides all share similar basic structures and contain steroid nuclei composed of 30 carbon atoms arranged in four rings. They are divided into two groups based on the different glycosidic structures: dammarane type and oleanane type. The dammarane type includes two categories: 20(s)-Protopanaxadiol (PPD) [9] and Propanaxantriol (PPT).

Ginsenosides have been clinically confirmed to enhance human immunity and assist in the treatment of cancer [10]. The anti-tumor mechanism of ginsenosides mainly focuses on regulating tumor cell autophagy [11], inhibiting tumor cell proliferation [12], and promoting tumor cell apoptosis [13]. Recent studies have found that the anti-apoptotic mechanism of mesenchymal stem cells increases the number of mitochondrial transfers [14], which conversely promotes cancer cell proliferation, contradicting the purpose of cancer treatment. Therefore, fathoming the mechanism of mitochondrial transfer and the regulatory mode of ginseng on this process may be a new direction for further elucidating the role of ginsenosides in anti-tumor therapy. In recent years, studies have further shown that ginsenosides and their components can directly target mitochondria and regulate their function, metabolism and autophagy, which provides a theoretical basis for studying their regulation of mitochondrial transfer between cells [15,16]. Ginsenosides have a protective effect on thymocytes. Different from tumor cells, thymocytes and thymic epithelial cells are immune cells and supportive cells for immune cell differentiation and development. The effect of ginsenosides on mitochondrial transfer between thymocytes and thymic epithelial cells is not yet clear. By exploring the effect of ginsenosides on mitochondrial transfer between thymocytes and thymic epithelial cells, we can further understand the impact and mechanism of ginsenosides on mitochondrial transfer from the perspective of immunoregulation, which undoubtedly contribute positively to elucidating the immunomodulatory role of ginseng. This paper aims to preliminarily explore the mechanism of ginsenosides on mitochondrial transfer between thymocytes and thymic epithelial cells using network pharmacology methods.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Acquisition of ginsenoside target predictions

The Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Analysis Platform [17] (https://tcmspw.com/tcmsp.php, TCMSP) was used to search for the chemical components in ginseng using the keyword "ginseng". By differentiating the chemical and structural formulas of PPD and PPT, the Molecule Names of PPD and PPT can be identified. The Organic Small Molecule Biological Activity Data [18] (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, PubChem) was applied to obtain the 3D structures and SMILES of the chemical components of PPD and PPT through their Molecule Names. Subsequently, with PharmMapper (http://lilab-ecust.cn/pharmmapper) Database [19], component target predictions were obtained through the 3D structures of the chemical components of PPD and PPT. The Swiss Target Prediction (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch) Database [20] was adopted to obtain component target predictions through SMILES of PPD and PPT, thereby identifying the targets of PPD and PPT. The component target predictions obtained by PharmMapper and Swiss Target Prediction were screened to improve the reliability of the prediction results. Specifically, targets with a Z-score > 0 in the PharmMapper database were retained, and for the Swiss Target Prediction database, targets with a Probability > 0 are retained. Subsequently, the screening results of the two databases were integrated, and the intersection was taken as an effective target for PPD and PPT.

2.2 Acquisition of targets of mitochondria, thymocytes and thymic epithelial cells

GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) database [21] was utilized to obtain the related targets of mitochondria, thymocytes and thymic epithelial cells. In this study, 'mitochondrial target' is defined as a gene-encoded protein that is closely related to mitochondrial function, including but not limited to proteins located in mitochondria, and proteins that indirectly affect mitochondria by regulating mitochondrial biosynthesis, dynamics, metabolism and function (such as oxidative phosphorylation). Similarly, 'thymic cell target gene' and 'thymic epithelial cell target gene' are also defined as functionally related, referring to genes that are known or predicted to be expressed in the cell and participate in its physiological activity or pathological process. This broad definition helps to fully capture the potential targets of ginsenosides that may affect mitochondria and immune cells directly or indirectly. The mitochondrial targets were separately screened against the effective targets of PPD and PPT to identify common targets between mitochondria and PPD, as well as between mitochondria and PPT. The GeneCards database was also used to acquire targets for thymocytes and thymic epithelial cells. The targets of thymocytes and thymic epithelial cells, as well as effective targets of PPD and PPT were separately screen to obtain common targets of thymocytes and PPD/PPT, as well as common targets of thymic epithelial cells and PPD/PPT.

2.3 Target pathway enrichment analysis

To further understand the functions of the selected target protein genes and their roles in signaling pathways, the common targets were imported into the Metascape database [22]. By inputting a list of target gene names and limiting the species to humans with a threshold of p < 0.01, Gene Ontology (GO) biological process enrichment analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) signaling pathway enrichment analysis were performed. The results obtained were subsequently analyzed.

3 Results

3.1 Results of targets obtainment

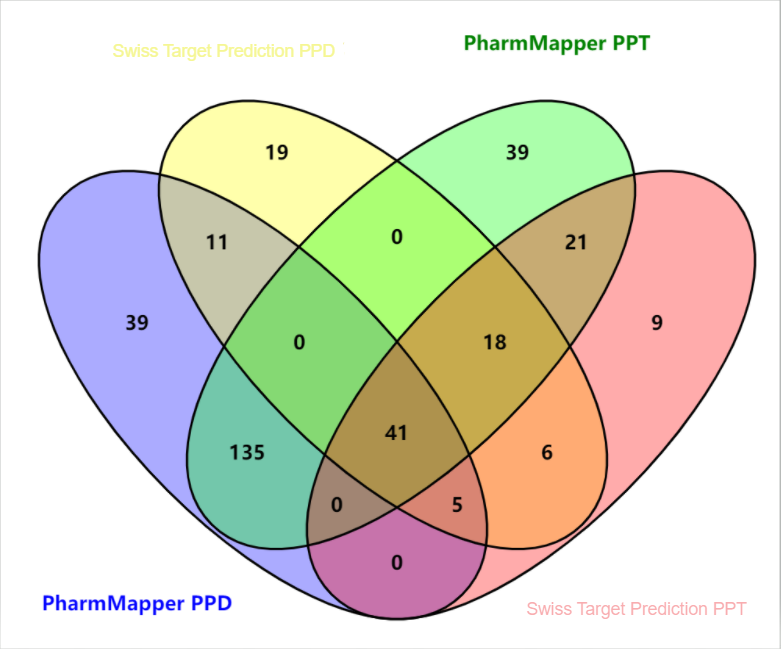

Through the PharmMapper database, 231 targets for PPD and 254 targets for PPT were identified. Using the Swiss Target Prediction database, there were 100 targets each for PPD and PPT. After data integration, 57 valid targets for PPD and 80 valid targets for PPT were obtained, as shown in Table 1, Table 2, and Figure 1.

A total of 2676 mitochondrial targets, 15 common targets for mitochondria and PPD, and 22 common targets for mitochondria and PPT were obtained through the GeneCards database, as described in Table 3 and Table 4.

A total of 1628 thymocyte targets and 336 thymic epithelial cell targets were obtained from the GeneCards database. There were 18 common targets between thymocytes and PPD, and 23 common targets between thymocytes and PPT (Table 5-6). Also, there were 2 common targets between thymic epithelial cells and PPD (c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 and MAP kinase p38 alpha), and 7 common targets between thymic epithelial cells and PPT (Cyclooxygenase-2, MAP kinase p38 alpha, PI3-kinase p110-gamma subunit, Tyrosine-protein kinase JAK1, Tyrosine-protein kinase JAK2, c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1, and Stem cell growth factor receptor).

Figure 1 The Venn diagram of targets of PPD and PPT in the PharmMapper database and the Swiss Target Prediction database. Unit: number

Table 1 57 valid targets of PPD.

| Targets | Common name |

|---|---|

| Protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B | PTPN1 |

| Norepinephrine transporter | SLC6A2 |

| Androgen Receptor | AR |

| Cytochrome P450 2C19 | CYP2C19 |

| Estrogen receptor alpha | ESR1 |

| Serotonin transporter | SLC6A4 |

| Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M2 | CHRM2 |

| Cytochrome P450 51 | CYP51A1 |

| HMG-CoA reductase | HMGCR |

| Cytochrome P450 19A1 | CYP19A1 |

| Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group I member 3 | NR1I3 |

| LXR-alpha | NR1H3 |

| Acetylcholinesterase | ACHE |

| 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 | HSD11B1 |

| Potassium-transporting ATPase alpha chain 2 | ATP12A |

| Niemann-Pick C1-like protein 1 | NPC1L1 |

| Nuclear receptor ROR-gamma | RORC |

| Cytochrome P450 17A1 | CYP17A1 |

| Estrogen receptor beta | ESR2 |

| Vitamin D receptor | VDR |

| Testis-specific androgen-binding protein | SHBG |

| Carboxylesterase 2 | CES2 |

| UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B7 | UGT2B7 |

| Cytochrome P450 24A1 | CYP24A1 |

| Butyrylcholinesterase | BCHE |

| Tyrosine-protein kinase BRK | PTK6 |

| C-C chemokine receptor type 1 | CCR1 |

| Phosphodiesterase 10A | PDE10A |

| Aldo-keto-reductase family 1 member C3 | AKR1C3 |

| Interleukin-6 receptor subunit beta | IL6ST |

| Epoxide hydratase | EPHX2 |

| Smoothened homolog | SMO |

| Adenosine A1 receptor | ADORA1 |

| Adenosine A2a receptor | ADORA2A |

| Protein kinase C gamma | PRKCG |

| Protein kinase C delta | PRKCD |

| Protein kinase C beta | PRKCB |

| Protein kinase C epsilon | PRKCE |

| Pregnane X receptor | NR1I2 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | CDK6 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 | CDK4 |

| ALK tyrosine kinase receptor | ALK |

| Bile acid receptor FXR | NR1H4 |

| Phosphodiesterase 2A | PDE2A |

| Phosphodiesterase 4B | PDE4B |

| Voltage-gated potassium channel subunit Kv1.3 | KCNA3 |

| 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 | HSD11B2 |

| P53-binding protein Mdm-2 | MDM2 |

| C-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 | MAPK8 |

| MAP kinase p38 alpha | MAPK14 |

| Cytochrome P450 2C9 | CYP2C9 |

| Cytochrome P450 3A4 | CYP3A4 |

| Subtilisin/kexin type 7 | PCSK7 |

| G-protein coupled receptor 55 | GPR55 |

| N-arachidonyl glycine receptor | GPR18 |

| Calcitonin gene-related peptide type 1 receptor | CALCRL |

| Serine/threonine-protein kinase Chk1 | CHEK1 |

Table 2 80 valid targets of PPT.

| Targets | Common name |

|---|---|

| Protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B | PTPN1 |

| Cytochrome P450 2C19 | CYP2C19 |

| Androgen Receptor | AR |

| Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M2 | CHRM2 |

| Norepinephrine transporter | SLC6A2 |

| Serotonin transporter | SLC6A4 |

| Cytochrome P450 19A1 | CYP19A1 |

| Acetylcholinesterase | ACHE |

| 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 | HSD11B1 |

| Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group I member 3 | NR1I3 |

| Estrogen receptor alpha | ESR1 |

| Potassium-transporting ATPase alpha chain 2 | ATP12A |

| Cytochrome P450 51 | CYP51A1 |

| Niemann-Pick C1-like protein 1 | NPC1L1 |

| HMG-CoA reductase | HMGCR |

| Nuclear receptor ROR-gamma | RORC |

| LXR-alpha | NR1H3 |

| Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 | SREBF2 |

| Cytochrome P450 17A1 | CYP17A1 |

| Vitamin D receptor | VDR |

| C-C chemokine receptor type 1 | CCR1 |

| UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B7 | UGT2B7 |

| Cyclooxygenase-2 | PTGS2 |

| Phosphodiesterase 10A | PDE10A |

| G-protein coupled receptor 55 | GPR55 |

| N-arachidonyl glycine receptor | GPR18 |

| Proteinase-activated receptor 1 | F2R |

| Butyrylcholinesterase | BCHE |

| Serine/threonine-protein kinase mTOR | MTOR |

| ALK tyrosine kinase receptor | ALK |

| Phosphodiesterase 2A | PDE2A |

| Phosphodiesterase 4B | PDE4B |

| PI3-kinase p110-beta subunit | PIK3CB |

| Pregnane X receptor | NR1I2 |

| Prostaglandin E synthase | PTGES |

| Gamma-secretase | PSEN2 |

| PSENEN | |

| NCSTN | |

| APH1A | |

| PSEN1 | |

| APH1B | |

| Corticotropin releasing factor receptor 1 | CRHR1 |

| MAP kinase p38 alpha | MAPK14 |

| Testis-specific androgen-binding protein | SHBG |

| Sodium channel protein type IX alpha subunit | SCN9A |

| Smoothened homolog | SMO |

| Mu opioid receptor (by homology) | OPRM1 |

| Delta opioid receptor (by homology) | OPRD1 |

| PI3-kinase p110-delta subunit | PIK3CD |

| PI3-kinase p110-gamma subunit | PIK3CG |

| Cytochrome P450 2C9 | CYP2C9 |

| Cytochrome P450 3A4 | CYP3A4 |

| PI3-kinase p110-alpha subunit | PIK3CA |

| P2X purinoceptor 3 | P2RX3 |

| Cytochrome P450 24A1 | CYP24A1 |

| Serine/threonine-protein kinase Aurora-A | AURKA |

| Tubulin--tyrosine ligase | TTL |

| Vasopressin V1a receptor | AVPR1A |

| CDK8/Cyclin C | CCNC |

| CDK8 | |

| Collagen type IV alpha-3-binding protein | COL4A3BP |

| Cell division protein kinase 8 | CDK8 |

| Leucine-rich repeat serine/threonine-protein kinase 2 | LRRK2 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 1/cyclin B | CCNB3 |

| CDK1 | |

| CCNB1 | |

| CCNB2 | |

| Tyrosine-protein kinase JAK1 | JAK1 |

| Tyrosine-protein kinase JAK2 | JAK2 |

| Carboxylesterase 2 | CES2 |

| C-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 | MAPK8 |

| Epoxide hydratase | EPHX2 |

| Cyclooxygenase-1 | PTGS1 |

| Insulin receptor | INSR |

| Cytochrome P450 2D6 | CYP2D6 |

| Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase | NAMPT |

| Phosphodiesterase 5A | PDE5A |

| Histone deacetylase 6 | HDAC6 |

| Neurokinin 2 receptor | TACR2 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 9 | CDK9 |

| Histone deacetylase 1 | HDAC1 |

| Serine/threonine protein phosphatase PP1-gamma catalytic subunit | PPP1CC |

| Serine/threonine protein phosphatase 2A, catalytic subunit, alpha isoform | PPP2CA |

| Stem cell growth factor receptor | KIT |

| Subtilisin/kexin type 7 | PCSK7 |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 | KDR |

| Melanin-concentrating hormone receptor 1 | MCHR1 |

| Calcitonin gene-related peptide type 1 receptor | CALCRL |

| Tyrosine-protein kinase BRK | PTK6 |

Table 3 15 common targets for mitochondria and PPD.

| Targets | Common name |

|---|---|

| Androgen Receptor | AR |

| C-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 | MAPK8 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 | CDK4 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | CDK6 |

| Cytochrome P450 24A1 | CYP24A1 |

| Estrogen receptor alpha | ESR1 |

| Estrogen receptor beta | ESR2 |

| HMG-CoA reductase | HMGCR |

| MAP kinase p38 alpha | MAPK14 |

| P53-binding protein Mdm-2 | MDM2 |

| Phosphodiesterase 2A | PDE2A |

| Protein kinase C delta | PRKCD |

| Protein kinase C epsilon | PRKCE |

| Protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B | PTPN1 |

| Voltage-gated potassium channel subunit Kv1.3 | KCNA3 |

Table 4 22 common targets for mitochondria and PPT.

| Targets | Common name |

|---|---|

| Protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B | PTPN1 |

| Androgen Receptor | AR |

| Estrogen receptor alpha | ESR1 |

| HMG-CoA reductase | HMGCR |

| Cyclooxygenase-2 | PTGS2 |

| Proteinase-activated receptor 1 | F2R |

| Serine/threonine-protein kinase mTOR | MTOR |

| Phosphodiesterase 2A | PDE2A |

| MAP kinase p38 alpha | MAPK14 |

| PI3-kinase p110-gamma subunit | PIK3CG |

| PI3-kinase p110-alpha subunit | PIK3CA |

| Cytochrome P450 24A1 | CYP24A1 |

| Serine/threonine-protein kinase Aurora-A | AURKA |

| Leucine-rich repeat serine/threonine-protein kinase 2 | LRRK2 |

| Tyrosine-protein kinase JAK1 | JAK1 |

| Tyrosine-protein kinase JAK2 | JAK2 |

| C-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 | MAPK8 |

| Insulin receptor | INSR |

| Histone deacetylase 6 | HDAC6 |

| Serine/threonine protein phosphatase 2A, catalytic subunit, alpha isoform | PPP2CA |

| Stem cell growth factor receptor | KIT |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 | KDR |

Table 5 18 common targets between thymocytes and PPD.

| Targets | Common name |

|---|---|

| Androgen Receptor | AR |

| C-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 | MAPK8 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | CDK6 |

| Estrogen receptor alpha | ESR1 |

| Estrogen receptor beta | ESR2 |

| MAP kinase p38 alpha | MAPK14 |

| P53-binding protein Mdm-2 | MDM2 |

| Protein kinase C delta | PRKCD |

| Protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B | PTPN1 |

| 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 | HSD11B1 |

| Acetylcholinesterase | ACHE |

| Adenosine A1 receptor | ADORA1 |

| Adenosine A2a receptor | ADORA2A |

| Calcitonin gene-related peptide type 1 receptor | CALCRL |

| Interleukin-6 receptor subunit beta | IL6ST |

| Nuclear receptor ROR-gamma | RORC |

| Protein kinase C gamma | PRKCG |

| Serine/threonine-protein kinase Chk1 | CHEK1 |

Table 6 23 common targets between thymocytes and PPT.

| Targets | Common name |

|---|---|

| Protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B | PTPN1 |

| Androgen Receptor | AR |

| Estrogen receptor alpha | ESR1 |

| Cyclooxygenase-2 | PTGS2 |

| Serine/threonine-protein kinase mTOR | MTOR |

| MAP kinase p38 alpha | MAPK14 |

| PI3-kinase p110-gamma subunit | PIK3CG |

| PI3-kinase p110-alpha subunit | PIK3CA |

| Tyrosine-protein kinase JAK1 | JAK1 |

| Tyrosine-protein kinase JAK2 | JAK2 |

| C-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 | MAPK8 |

| Insulin receptor | INSR |

| Serine/threonine protein phosphatase 2A, catalytic subunit, alpha isoform | PPP2CA |

| Stem cell growth factor receptor | KIT |

| Acetylcholinesterase | ACHE |

| 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 | HSD11B1 |

| Nuclear receptor ROR-gamma | RORC |

| PI3-kinase p110-delta subunit | PIK3CD |

| Cyclooxygenase-1 | PTGS1 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 9 | CDK9 |

| Histone deacetylase 1 | HDAC1 |

| Serine/threonine protein phosphatase PP1-gamma catalytic subunit | PPP1CC |

| Calcitonin gene-related peptide type 1 receptor | CALCRL |

3.2 KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

The common targets shared by PPD/PPT with mitochondria, thymocytes, and thymic epithelial cells were imported into Metascape for KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. Items with a corrected p value < 0.01 were screened, and after removal of duplicates, a total of 22 signaling pathways were identified. However, due to the limited number of shared targets between PPD and thymic epithelial cells, effective KEGG pathway enrichment analysis could not be obtained. The results were depicted in Figure 2. In KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, all results contained cancer pathways.

Figure 2 KEGG pathway enrichment analysis results. (A) 5 pathways from the KEGG enrichment analysis of PPD and mitochondrial targets; (B) 7 pathways from the KEGG enrichment analysis of PPT and mitochondrial targets; (C) 5 pathways from the KEGG enrichment analysis of PPD and thymocyte targets; (D) 7 pathways from the KEGG enrichment analysis of PPT and thymocyte targets; (E) 6 pathways from the KEGG enrichment analysis of PPT and thymic epithelial cell targets.

3.3 GO functional enrichment analysis

The common targets of PPD/PPT shared with mitochondria, thymocytes, and thymic epithelial cells were imported into Metascape for GO functional enrichment analysis. The items with a corrected p value < 0.01 were selected, and the duplicate items were removed. Finally, a total of 52 GO functions were screened out. However, due to the insufficient common targets of PPD and thymic epithelial cells, an effective GO functional enrichment analysis could not be conducted. The results were delineated in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Functional enrichment analysis results. (A) 11 GO items from the GO enrichment analysis of PPD and mitochondrial targets; (B) 20 GO items from the GO functional analysis of PPT and mitochondrial targets; (C) 10 GO items from the GO functional analysis of PPD and thymocyte targets; (D) 20 GO items from the GO functional analysis of PPT and thymocyte targets; (E) 8 GO items from the GO functional analysis of PPT and thymic epithelial cell targets.

4 Discussion

In recent years, significant progress has been made in the early diagnosis and chemotherapy of cancer, but many cancers are still incurable. Fortunately, ginsenosides have comprehensive anti-cancer effects. In addition to regulating autophagy, suppressing proliferation, and promoting apoptosis of tumor cells, ginsenosides can also enhance the body's immune system. Thymocytes and thymic epithelial cells play an important role in the immune system, mediating the immune balance of the body and maintaining immune stability. Ginsenosides can increase the proportion of thymic cortex area, enhance thymic cell proliferation ability, and exert a reliable protective effect on thymocytes [23]. Therefore, it is speculated that ginsenosides can also affect mitochondrial transfer between thymocytes and thymic epithelial cells.

In this study, it was predicted by network pharmacology that PPD and PPT may affect the function of mitochondria and the transfer between cells in the thymic microenvironment through different signaling pathways and biological functions. Specifically, PPD may mainly promote mitochondrial biosynthesis, while PPT focuses on regulating mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy.

Generally, under the influence of microenvironment, damaged endothelial cell mitochondria can trigger the anti-apoptotic mechanism of mesenchymal stem cells, thereby alleviating cell damage. For cancer cells, mesenchymal stem cells mediate mitochondrial transfer to cancer cells through tunnel nanotubes (TNTs), extracellular vesicles (EVs), and cell fusion, restoring their oxidative phosphorylation and causing drug resistance and proliferation of cancer cells. PPD and PPT both can assist in cancer treatment in clinical practice. They interfere with tumor cell proliferation, mediate mitochondrial autophagy pathway [24], and promote cell apoptosis [25] via inhibiting the expression of cell cycle-related protein CDK4/CyclinD, reducing Haspin kinase activity, and disrupting mitosis.

The core prediction of this study is that PPD and PPT may regulate mitochondrial function through distinct signaling pathways. Besides the cancer pathway, PPD and PPT can directly affect mitochondria through different pathways. PPD can promote the activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain enzyme complex I through the cAMP signaling pathway [26], enhance the electron transfer process, which promotes intracellular phosphorylation level, and further enhance mitochondrial biogenesis and activity, manifested as an increase in mitochondrial quantity. PPT can mobilize white adipose tissue and increase fat breakdown and phosphorylation through the cGMP PKG signaling pathway [27], ultimately achieving the effect of increasing mitochondrial quantity.

In different pathways, PPD impacts AMPK signaling pathway [28]. It acts on β2 receptors, increases the transcription and activity of PGC-1α, and regulates NRF and TFAM transcription via activating the cAMP/PKA pathway and the pathway protein CREB. It also promotes mitochondrial biogenesis, activates AMPKα [29], boosts cellular glucose uptake and elevates the phosphorylation level of AMPKα, with the involvement of TFAM, thereby activating fatty acid oxidation pathways and further enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolic activity.

Compared to PPD, PPT influences mitochondria mainly through mitochondrial dynamics balance. On the one hand, PPT can activate the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway [30], upregulate the expression of the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2, and downregulate the expression of the pro-apoptotic gene Bax, thereby reducing mitochondrial autophagy. On the other hand, PPT activates its downstream protein Rap1 through the Rap1 signaling pathway [31], promoting signal transduction, inhibiting mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [32], thereby suppressing mitochondrial fusion, enhancing mitochondrial fission, disrupting mitochondrial homeostasis and function, and activating the mitochondria-mediated apoptosis pathway.

The GO functions of PPD and PPT together include positive regulation of phosphorylation, protein-kinase binding, and response to hormones. The GO function contains cellular responses to estrogen stimulation, as PPD and PPT have estrogen-like effects [33], which can inhibit endothelial cell oxidative stress, activate inflammatory responses, mediate cell apoptosis, and reduce Akt and ERK1/2 protein phosphorylation levels through binding to estrogen receptors, thus achieving estrogen-like vascular protection. Their antagonistic effect on Ca²⁺ protects mitochondria in ischemic brain neurons from damage and loss by enhancing the fluidity of the mitochondrial membrane in the ischemic brain, reducing mitochondrial membrane phospholipid degradation, mitigating mitochondrial swelling, and inhibiting the decrease in activity of NADH complex I, cytochrome C oxidase, and succinate dehydrogenase [34]. Furthermore, it decreases mitochondrial MDA content, enhances mitochondrial SOD activity, and repress excessive Ca²⁺ uptake, thereby protecting mitochondria, although the efficacy is weaker than that of estrogen. The numerous GO functions of PPD and PPT provided conditions for direct or indirect mitochondrial transfer. For example, the function of PPD related to protein serine kinase activity was broad, encompassing regulating cell proliferation and differentiation, promoting cell survival, and mediating and correcting cell metabolism. The PPT can positively regulate phosphorus metabolism function, and accelerate mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to provide conditions for mitochondrial ATP synthesis.

It must be emphasized that all the conclusions of this study are derived from bioinformatics predictions. As a powerful hypothesis generation tool, network pharmacology has successfully outlined the potential blueprint of PPD and PPT for us. However, these computational predictions have inherent limitations. First of all, the target prediction database itself is still in continuous improvement; secondly, enrichment analysis suggested pathway associations, but could not confirm specific causal regulatory relationships (e. g., activation or inhibition). Therefore, the mechanism of action proposed in this paper, including PPD promoting mitochondrial formation through cAMP signaling pathway, and PPT regulating mitochondrial dynamics through cGMP-PKG and Rap1 signaling pathways, is a scientific hypothesis that needs to be verified by experiments. Future studies urgently need to use in vitro co-culture models, gene knockout, mitochondrial fluorescence labeling and other techniques to directly observe and confirm the direct effect of ginsenosides on mitochondrial transfer between thymocytes and thymic epithelial cells, and to empirically test the above predictive pathways.

Mitochondrial transfer is of great significance to the immune system, and generates different effects in different cells. Normal cells treat themselves through mitochondrial transfer. For example, mesenchymal stem cell mitochondrial transfer has therapeutic effects on various diseases such as cerebral ischemia, myocardial infarction, and acute renal failure [4]. Moreover, mesenchymal stem cells can dampen immune cell differentiation through mitochondrial transfer, and exert immunosuppressive effects through downregulating T-bet expression to suppress Th1 response [5]. Mitochondrial transfer has a broad prospect in the treatment of tissue damage repair [35] and mitochondrial diseases. As a novel treatment method, the mechanism of mitochondrial transfer needs further elucidation.

Based on network pharmacology, KEGG and GO enrichment analysis results revealed that PPD and PPT elevate mitochondrial quantity growth through various pathways, which may directly or indirectly promote mitochondrial transfer and improve mitochondrial dysfunction. PPD can increase mitochondrial quantity by promoting cellular phosphorylation levels, such as promoting mitochondrial generation via the cAMP signaling pathway, enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolic activity. PPT also has regulatory effects on mitochondria possibly through the cGMP-PKG signaling pathway and Rap1 signaling pathway, facilitating mitochondrial autophagy. These findings indicated that PPD and PPT have different effects on mitochondria.

Among the known cancer pathways, mitochondrial transfer of mesenchymal stem cells may affect cancer treatment. Therefore, exploring key factors that inhibit mitochondrial transfer of mesenchymal stem cells (such as blocking the formation of TNTs) may provide a new target for cancer treatment. In contrast, PPT that regulates mitochondrial function is more likely to affect tube morphogenesis. The effects of PPD and PPT on cellular metabolism [36] may also be a new research direction, as cellular metabolic activity can indirectly reflect mitochondrial activity. This study also mentioned related pathways, such as inhibited PI3K Akt signaling pathway that can promote mitochondrial autophagy and cell apoptosis. Moreover, the endocrine resistance is attributed to the participation of mitochondria in oocyte development via multi-pathways, and the endocrine dysfunction can induce abnormal or disrupted oocyte development, further damage ovary function and trigger reproductive endocrine diseases [37]. PPD and PPT can improve mitochondrial dysfunction [38], implying their potential in treating endocrine diseases through the mechanism of mitochondrial transfer. In conclusion, to further investigate the efficacy of ginsenosides, it is necessary to deeply understand the mechanism of mitochondrial transfer.

A major limitation of this study is that its conclusions are entirely based on predictive analysis of network pharmacology and bioinformatics. Although these computational methods can efficiently reveal potential drug-target-pathway interactions and provide valuable directions and hypotheses for subsequent research, they still need to be verified by in vitro and in vivo experiments to provide direct biological evidence. Future research will focus on experimental demonstration of this prediction.

Back Matter

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author of this article, Jianli Gao, is a member of the editorial office of this journal. All procedures during the editorial review process were conducted strictly in accordance with the journal's policies, and the author was not involved in handling any part of the process.

Author Contributions

Substantial contributions to conception and design: Z.Z. Data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation: X.W. Drafting the article or critically revising it for important intellectual content: J.G. Final approval of the version to be published: All authors. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: All authors.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

No ethical approval was required for this article.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82474614).

Availability of Data and Materials

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Supplementary Materials

Not applicable.

References

- Feng GQ. Mitochondria are not merely the "powerhouse" of the cell. Biology Teaching 2023; 48(7): 75-77.

- Akhter W, Nakhle J, Vaillant L, et al. Transfer of mesenchymal stem cell mitochondria to CD4+ T cells contributes to repress Th1 differentiation by downregulating T-bet expression. Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2023; 14(1): 12.

- D'Amato M, Morra F, Di Meo I, et al. Mitochondrial Transplantation in Mitochondrial Medicine: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023; 24(3): 1969.

- Wang ZL, Yu LM, Zhao CH. Tissue repair using mesenchymal stem cells via mitochondrial transfer. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research 2020; 24(7): 1123-1129.

- Luz-Crawford P, Hernandez J, Djouad F, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell repression of Th17 cells is triggered by mitochondrial transfer. Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2019; 10(1): 232.

- Liu ZH, Sun XB. Network pharmacology: new opportunity for the modernization of traditional Chinese medicine. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica 2012; 47(6): 696-703.

- Niu JZ, Wei YL, Cao W, et al. Experimental Study on Ginseng Inhibiting Thymocyte Apoptosis in Mice. Acta Anatomica Sinica 1997; (3): 47-52+123.

- Li Y, Zhang TJ, Liu SX, et al. Research Progress on Chemical Components and Pharmacological Effects of Ginseng. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs 2009; 40(1): 164-166.

- Feng JS. Ginsenoside diol induces mitochondrial biosynthesis by activating β2 receptors and thereby prevents non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Jilin University 2023.

- Nag SA, Qin JJ, Wang W, et al. Ginsenosides as Anticancer Agents: In vitro and in vivo Activities, Structure-Activity Relationships, and Molecular Mechanisms of Action. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2012; 3: 25.

- Chen YC, Ren HG, Xi ZC, et al. Study Progress on Biopreparation and Antitumor Mechanism of Ginsenoside CK. Modernization of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Materia Medica-World Science and Technology 2023; 25(7): 2586-2595.

- Zhao L, Xu JH, Zhang L. Research Progress on the Anti-tumor Mechanism of Ginsenosides. Chinese Journal of Modern Applied Pharmacy 2023; 40(14): 2016-2022.

- Wang YH, Ai ZY, Zhang JS, et al. Research Progress on Antitumor Activity and Mechanism of Ginsenosides. Science and Technology of Food Industry 2023; 44(1): 485-491.

- Sun WM, Wang JP, Zhang WH, et al. Research progress related to the mechanism of mesenchymal stem cell-mediated mitochondrial transfer and its application in cancer treatment. Tianjin Medical Journal 2022; 50(11): 1217-1221.

- Ni XC, Wang HF, Cai YY, et al. Ginsenoside Rb1 inhibits astrocyte activation and promotes transfer of astrocytic mitochondria to neurons against ischemic stroke. Redox Biology 2022; 54: 102363.

- Wang F, Roh YS. Mitochondrial connection to ginsenosides. Archives of Pharmacal Research 2020; 43(10): 1031-1045.

- Ru J, Li P, Wang J, et al. TCMSP: A database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. Journal of Cheminformatics 2014; 6: 13.

- Liu HB, Peng Y, Huang LQ, et al. A rapid targeting method of natural products based on PubChem database. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs 2012; 43(11): 2099-2106.

- Wang X, Shen Y, Wang S, et al. PharmMapper 2017 update: a web server for potential drug target identification with a comprehensive target pharmacophore database. Nucleic Acids Research 2017; 45(W1): W356-W360.

- Gfeller D, Grosdidier A, Wirth M, et al. SwissTargetPrediction: a web server for target prediction of bioactive small molecules. Nucleic Acids Research 2014; 42(Web Server issue): W32-8.

- Trends M, Chalifa-Caspi V, Prilusky J, et al. GeneCards: Integrating information about genes, proteins and diseases. Trends Genet 1997; 13(4): 163.

- Dang K, Farooq HMU, Dong J, et al. Transcriptomic and proteomic time-course analyses based on Metascape reveal mechanisms against muscle atrophy in hibernating Spermophilus dauricus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A-molecular & Integrative Physiology 2023; 275: 111336.

- Zhang LH, Ran RT, Sun JZ, et al. Effects of ginsenoside Rg1 on thymus structure and function of rats. Acta Anatomica Sinica 2015; 46(3): 367-372.

- Li XH, Wu XX, Zhang K, et al. Progress on Relationship between Mitophagy and Cancer. Progress in Veterinary Medicine 2017; 38(9): 109-114.

- Lin SZ, Wang CR. Effect of Ginsenoside Rb1 mediated mitochondrial autophagy pathway on apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. The Chinese Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2023; 39(12): 1713-1717.

- Yang P. Exploring the effect of the Huayu Qutan recipe on the mitochondrial energy metabolism of cardiomyocytes in AS rabbits based on the cAMP-PKA signaling pathway. Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2023.

- Sun JB. Exploring the Mechanism of the Effect of Abdominal Vibration Method on Regulating White Fat Mobilization in Obese Mice Based on the cGMP-PKG Signal. Changchun University of Chinese Medicine 2023.

- Xu DY. Ginsenoside Rg3 Relieve Cancer-related Fatigue by Activating AMPK. Dalian Medical University 2021.

- Lu FL, Yan YX, Yu Q, et al. Protective effect of swimming on myocardial infarction: Role of AMPK/PGC-1alpha pathway. Medical Journal of Wuhan University 2024; 45(5): 520-526.

- Chen L. Research on the Effect of Exercise Pre-adaptation on Mitochondrial Autophagy in Reducing Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis via the PI3K-Akt Pathway. Kunming Medical University 2022.

- Xue W. Vitexin attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats by regulating mitochondrial dysfunction via Epac1-Rap1 signaling pathway. Anhui Medical University 2021.

- Yang Y, Zhang K, Gao J, et al. The Expression and Function Mechanisms of RAP1 in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Chinese Journal of Cell Biology 2021; 43(10): 1933-1943.

- Pan YT. The estrogen-like protective effects of ginsenoside Rb3 on vascular endothelial cells. Gansu University of Chinese Medicine 2014.

- Zhao W, Song XX, Hou Y, et al. Estrogen participates in the protective mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease by regulating mitochondria. Chinese Journal of Gerontology 2022; 42(24): 6164-6168.

- Huang QL, Shen L, Deng Y. Progress on Mitochondrial Transfer Mechanisms of Mesenchymal Stem Cell. Chinese Journal of Cell Biology 2019; 41(9): 1822-1831.

- Yao W, Guan Y. Ginsenosides in cancer: A focus on the regulation of cell metabolism. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022; 156: 113756.

- Wu XM, Guo M, Hou HY. Research Progress on the Correlation between Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Insulin Resistance/Related Reproductive Endocrine Diseases. Guangxi Medical Journal 2023; 45(5): 600-602.

- Huang Q, Gao S, Zhao D, et al. Review of ginsenosides targeting mitochondrial function to treat multiple disorders: Current status and perspectives. Journal of Ginseng Research 2021; 45(3): 371-379.