Main Text

1 Introduction

The immune system serves as the primary defense mechanism of the body, safeguarding against pathogenic invasion and maintaining internal homeostasis. It comprises lymphoid organs, immune cells, antibodies, cytokines, and various humoral factors that together form an integrated defensive network [1]. Its principal functions include antimicrobial defense, clearance of damaged or senescent cells, and immune surveillance to identify and eliminate malignant cells [2]. Inflammation is a fundamental physiological response to infection or tissue injury that facilitates pathogen clearance and initiates tissue repair [3]. However, chronic low-grade inflammation, represents a state of persistent immune dysregulation and serves a central pathogenic driver in a spectrum of conditions, including cardiorenal diseases, metabolic disorders, and cancer [4]. Notably, persistent immune abnormalities and low-grade inflammation have also been implicated in the long-term sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection [5,6]. While conventional pharmacotherapies such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and glucocorticoids provide symptomatic relief, their long-term utility is hampered by significant adverse effects, including gastrointestinal injury, organ toxicity, and immunosuppression [7]. These limitations have spurred interest in developing safe functional foods with immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory activities, often leveraging natural ingredients such as vitamins, minerals, botanicals, and animal-derived extracts.

Guided by the principles of nutritional immunology, we developed a composite functional formula, SVS, which integrates serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin protein isolate (SBI), vitamin C, and selenium-enriched yeast (Se-yeast). Orally administered SBI exerts beneficial effects by binding and neutralizing proinflammatory antigens such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), reducing intestinal permeability, and promoting gut microbial balance [8-10]. Notably, the protein fraction of SBI comprises more than 50% IgG, with the remainder consisting of serum proteins such as albumin, transferrin, and α2-macroglobulin [11]. Furthermore, SBI is generally recognized as safe (GRAS) for use in medical foods, a status supported by clinical studies [12-15]. Its therapeutic potential is underscored by ongoing clinical investigations, including studies involving COVID-19 (NCT04682041). We hypothesized that the efficacy of SBI could be potentiated by the addition of targeted micronutrients. Vitamin C was incorporated to provide robust antioxidant support, scavenge free radicals, and directly bolster immune-cell functions, thereby mitigating the oxidative stress that frequently accompanies inflammation [16,17]. Concurrently, Se-yeast, with its superior bioavailability [18], was included to further modulate redox balance and immune responses through its incorporation into selenoproteins [19], potentially amplifying the anti-inflammatory network.

We therefore formulated the composite ingredient SVS, consisting of SBI, vitamin C, and Se-yeast. Preliminary data indicated that SVS enhanced both cellular and humoral immunity in healthy mice [20]. This initial evidence, coupled with our previous demonstration that a formulated combination outperforms its individual constituents [21], led us to propose that SVS formula would act synergistically via complementary mechanisms to achieve context-dependent immunomodulation: enhancing baseline immune capacity while effectively constraining excessive inflammatory responses. Therefore, the present study aimed to systematically evaluate the immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects of the SVS formula using both in vivo and in vitro models, and to elucidate its underlying mechanisms through transcriptomic analysis.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials and reagents

SBI was supplied by Proliant New Zealand Limited (Feilding, New Zealand). Vitamin C was obtained from Heilongjiang Xinhecheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Heilongjiang, China). Se-yeast (0.2% selenium) was purchased from Angel Yeast Co., Ltd. (Hubei, China). MTT, ConA, and Giemsa dyes were obtained from Beijing Suolaibao Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). RPMI-1640 medium, high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit were procured from Thermo Fisher Scientific (China) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Additional reagents, including lipopolysaccharide (LPS), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), penicillin‒streptomycin solution, TRIzol reagent, diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water, and BeyoFast™ SYBR Green qRT-PCR Mix, were acquired from Shanghai Beyond Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Chloroform, isopropanol, and absolute ethanol were purchased from Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory (Tianjin, China).

2.2 Animal experiments

2.2.1 Experimental design

Male Kunming mice (20–22 g) were obtained from the Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center and maintained under standardized housing conditions [22]. All experimental procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments of Zunyi Medical University and conducted in accordance with institutional animal welfare guidelines.

SVS was prepared at a mass ratio of SBI: vitamin C: Se-yeast = 1: 0.4: 0.04. On the basis of the recommended adult daily intakes (1 g SBI and 1.44 g SVS) and a standard adult body weight of 60 kg, the low- and high-dose groups were designed with 10-fold and 30-fold human-equivalent doses, respectively, in accordance with the Technical Standards for Testing and Assessment of Health Food (China, version 2023). A total of 120 mice were randomly divided into two experimental batches (Batch I and Batch II; n = 60 each). Each batch was further subdivided into five groups (n = 12/group): (1) control (Con) group receiving drinking water, (2) low-dose SBI (0.167 g/kg), (3) high-dose SBI (0.501 g/kg), (4) low-dose SVS (0.240 g/kg), and (5) high-dose SVS (0.720 g/kg). All the treatments were administered orally once daily for 30 consecutive days. The mice in Batch I were used for the ConA-induced splenic lymphocyte proliferation assay, whereas those in Batch II were used for the peritoneal macrophage phagocytosis assay. Both immunological evaluations were conducted in accordance with the aforementioned national standards.

2.2.2 Splenic lymphocyte proliferation assay

On Day 30, the spleens were aseptically harvested and placed in sterile Hanks'solution. Single-cell suspensions were prepared by gently grinding the tissue, filtering through a 200-mesh sieve, and washing twice with sterile buffer. The cells were subsequently centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min and resuspended to a final concentration of 3 × 106 cells/mL. Aliquots (1 mL) were seeded into two wells of a 24-well plate. One well was supplemented with 75 μL of ConA solution (7.5 μg/mL), while the other well served as a negative control. The plates were incubated at 37 ℃ in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 72 h. Four hours prior to the end of incubation, 0.7 mL of the supernatant was replaced with fresh RPMI-1640 without FBS, followed by the addition of 50 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL). After 4 h of incubation, 1 mL of acidic isopropanol was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. The optical density (OD) was measured at 570 nm via a microplate reader. The lymphoproliferative response was expressed as the difference in OD values between ConA-stimulated and unstimulated cultures.

2.2.3 Peritoneal macrophage phagocytosis assay

The mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 mL of 20% (v/v) chicken red blood cells (CRBCs). After 30 min, peritoneal lavage was performed with 2 mL of sterile saline following gentle abdominal massage. A 1-mL aliquot of the lavage fluid was applied to two pretreated slides and incubated at 37 ℃ for 30 min in a humidified chamber. The slides were then washed three times, fixed in a 1: 1 acetone-methanol solution for 10 min, and stained with 4% Giemsa stain for 3 min. After rinsing and drying, macrophage phagocytosis was assessed microscopically under oil immersion, with 100 cells counted per slide. The phagocytic index was calculated as follows:

Phagocytic Index= Total number of CRBCs ingested by counted macrophages/Total number of macrophages examined

2.3 RAW 264.7 macrophage experiments

2.3.1 Cell viability assay

RAW 264.7 macrophages were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37 ℃ in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well in 100 μL of medium. The treatment groups included the control, SBI (0.3–1000 μg/mL), vitamin C (0.3–1000 μg/mL), Se-yeast (0.01–30 μg/mL), SVS (0.3–1000 μg/mL), and a blank group (no cells). After 24 h of incubation, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing the indicated agents, and the cells were incubated for an additional 24 h. MTT solution (1 mg/mL, 100 μL/well) was then added, and the mixture was incubated for 4 h. The resulting formazan crystals were dissolved in DMSO (100 μL/well), and the OD was measured at 570 nm. For the inflammation experiment, dexamethasone (DXM) was used as a positive control. The cells were cotreated with LPS (1 μg/mL) and intervention agents (SBI, vitamin C, and SVS: 1–30 μg/mL; Se-yeast: 0.1–3 μg/mL; DXM: 30 μM).

Based on the results of this cell viability screening, non-cytotoxic concentrations (1, 3, 10, and 30 μg/mL for SBI, vitamin C, and SVS; 0.1, 0.3, 1, and 3 μg/mL for Se-yeast) were selected for use in the subsequent LPS-stimulated inflammation experiments.

2.3.2 Nitric oxide (NO) quantification via the Griess assay

NO levels were measured via a commercial kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). RAW 264.7 cells (2.5 × 104 cells/well) were treated as described in Section 2.3.1. After 24 h of incubation, 50 μL of culture supernatant was mixed with equal volumes of Griess Reagent. The mixture was incubated at room temperature (approximately 25 ℃) for 10 min, and the absorbance was read at 540 nm. NO concentrations were calculated from a sodium nitrite (NaNO2) standard curve.

2.3.3 Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) for TNF-α and IL-6

The cells were treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) alone or in combination with SVS (30 μg/mL). Subsequently, the culture supernatants were collected, centrifuged at 500 × g for 15 min at 4 ℃, and then assayed in duplicate. The levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in the supernatants were determined using commercial ELISA kits (TNF-α: MM-0163M1, IL-6: MM-0163M2; Meimian Industrial, China) according to the manufacturers' instructions, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

For gene expression analysis, total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (R0016, Beyond Biotechnology, China), and its purity was confirmed (A260/A280 = 1.8–2.1). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (K1622, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). qRT-PCR was performed using BeyoFast™ SYBR Green qRT-PCR Mix (D7266, Beyond Biotechnology, China) with the primers listed in Table S1. The amplification protocol was as follows: initial denaturation at 95 ℃ for 5 min; followed by 40 cycles of 95 ℃ for 15 s and 60 ℃ for 30 s. The relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method with GAPDH as the internal reference control.

2.3.4 Transcriptomic analysis

RAW 264.7 cells (2 × 106 cells/well) were grouped into the following groups: (1) control; (2) LPS (1 μg/mL); and (3) LPS + SVS (1 μg/mL LPS + 30 μg/mL SVS). RNA extraction followed the protocols in Section 2.3.3. Libraries were prepared via poly(A)+ selection, fragmented, reverse-transcribed, and sequenced (150-bp paired-end) via the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. Bioinformatic processing involved Cutadapt (v1.9.1), HISAT2 (v2.2.1), and HTSeq (v0.13.5). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified via DESeq2 with thresholds of |log2FC| ≥ log2(1.5) and p < 0.05. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses were conducted via OmicShare tools. Alternative splicing was analyzed with rMATS, and principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to visualize sample clustering on the basis of gene expression profiles [23]. Pathways were visualized with PathVisio (v3.3.0).

2.3.5 qRT-PCR validation of DEGs

Selected DEGs (CCL22, IL7R, CSF2RB2, INHBA, TNFRSF9, IL1F6, LIF, and IL1A) were chosen for validation based on their significant p-values and involvement in key enriched pathways. The mRNA expression levels of these genes were then validated via qRT-PCR, as described in Section 2.3.3. The primer sequences are listed in Table S1. Three biological replicates were analyzed.

2.4 Statistical methods

The data were analyzed via SPSS software (Version 29; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The results are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SD). One-way ANOVA followed by the least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test was used for comparisons, with significance set at p < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 SBI and SVS enhance splenic lymphocyte proliferation and peritoneal macrophage phagocytosis

Splenic lymphocytes were isolated 30 days after animal intervention (Figure 1A). Compared with the control, high-dose SVS (0.720 g/kg) significantly enhanced ConA-induced splenocyte proliferation (p < 0.05; Figure 1B). Similarly, peritoneal macrophages were collected (Figure 1C). Both high-dose SBI (0.501 g/kg) and high-dose SVS (0.720 g/kg) significantly elevated the phagocytic index of peritoneal macrophages relative to that of the control group (p < 0.05; Figure 1D). No signs of toxicity, such as abnormal body weight or organ pathology, were observed in the animal study (data not shown).

Figure 1 Immunomodulatory effects of SBI and SVS in mice. The mice were orally received drinking water, SBI (0.167 or 0.501 g/kg), or SVS (0.240 or 0.720 g/kg) daily for 30 consecutive days. (A) Experimental design of the ConA-induced splenic lymphocyte proliferation assay. (B) Effects of SBI and SVS on ConA-induced splenic lymphocyte proliferation. The proliferative response was quantified as the difference in optical density (ΔOD) between ConA-stimulated and unstimulated cultures. (C) Experimental design of the peritoneal macrophage phagocytosis assay. (D) Effects of SBI and SVS on the phagocytic index in mice. The data are shown as the means ± SD (n = 12). * p < 0.05 vs. the control group. Con, control; SBI, serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin protein isolate; SVS, SBI combined with vitamin C and Se-yeast.

3.2 Effects of SBI, vitamin C, Se-yeast, and SVS on the basal viability of RAW 264.7 macrophages

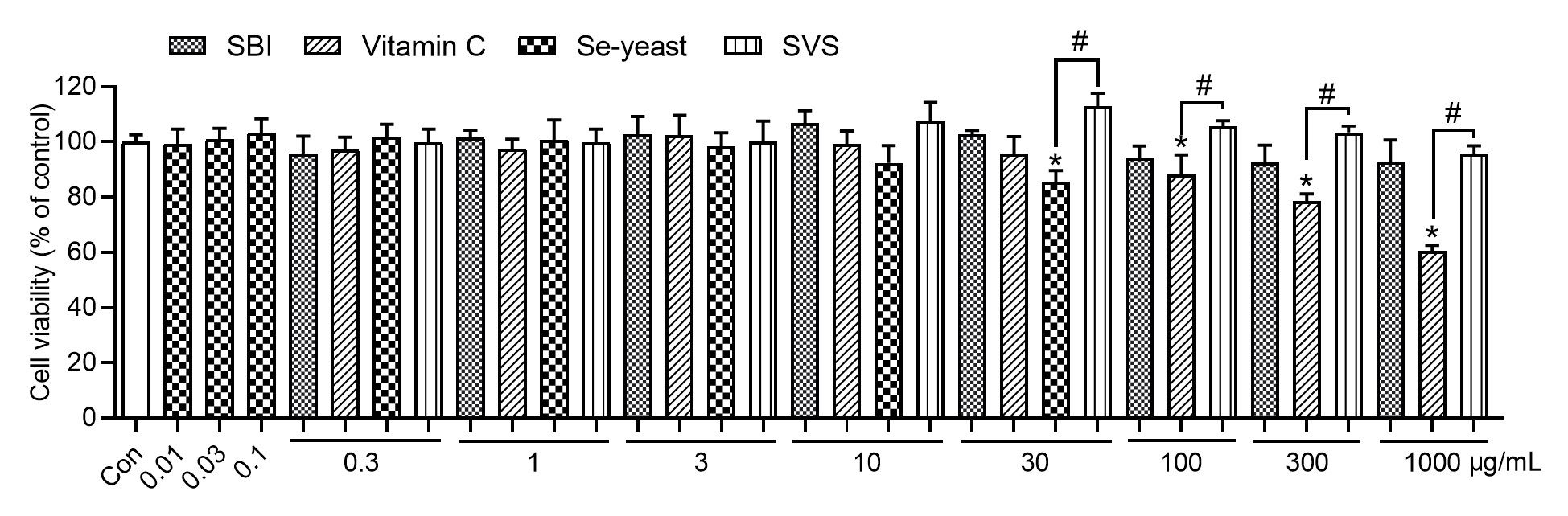

The effects of various agents on cell viability were evaluated across a concentration range of 0.01–1000 μg/mL. At concentrations ≤ 10 μg/mL, none of the treatments resulted in a statistically significant decrease in cell viability compared with the control, indicating that there were no cytotoxic effects at lower concentrations (Figure 2). At 30 μg/mL, the maximum concentration achievable under solvent conditions, Se-yeast treatment led to a significant reduction in cell viability (p < 0.05 vs. control), whereas SBI and SVS maintained viability levels comparable to those of the control. At higher concentrations (100–1000 μg/mL), vitamin C induced significant cytotoxicity relative to the control (p < 0.05), with a greater reduction in viability than that of SVS (p < 0.05).

Figure 2 Effects of SBI, vitamin C, Se-yeast, and SVS on cell viability. The data are shown as the means ± SD (n = 3); * p < 0.05 vs. the control group. # p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between treatment groups at the same concentration. Con, control; SBI, serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin protein isolate; SVS, SBI combined with vitamin C and Se-yeast.

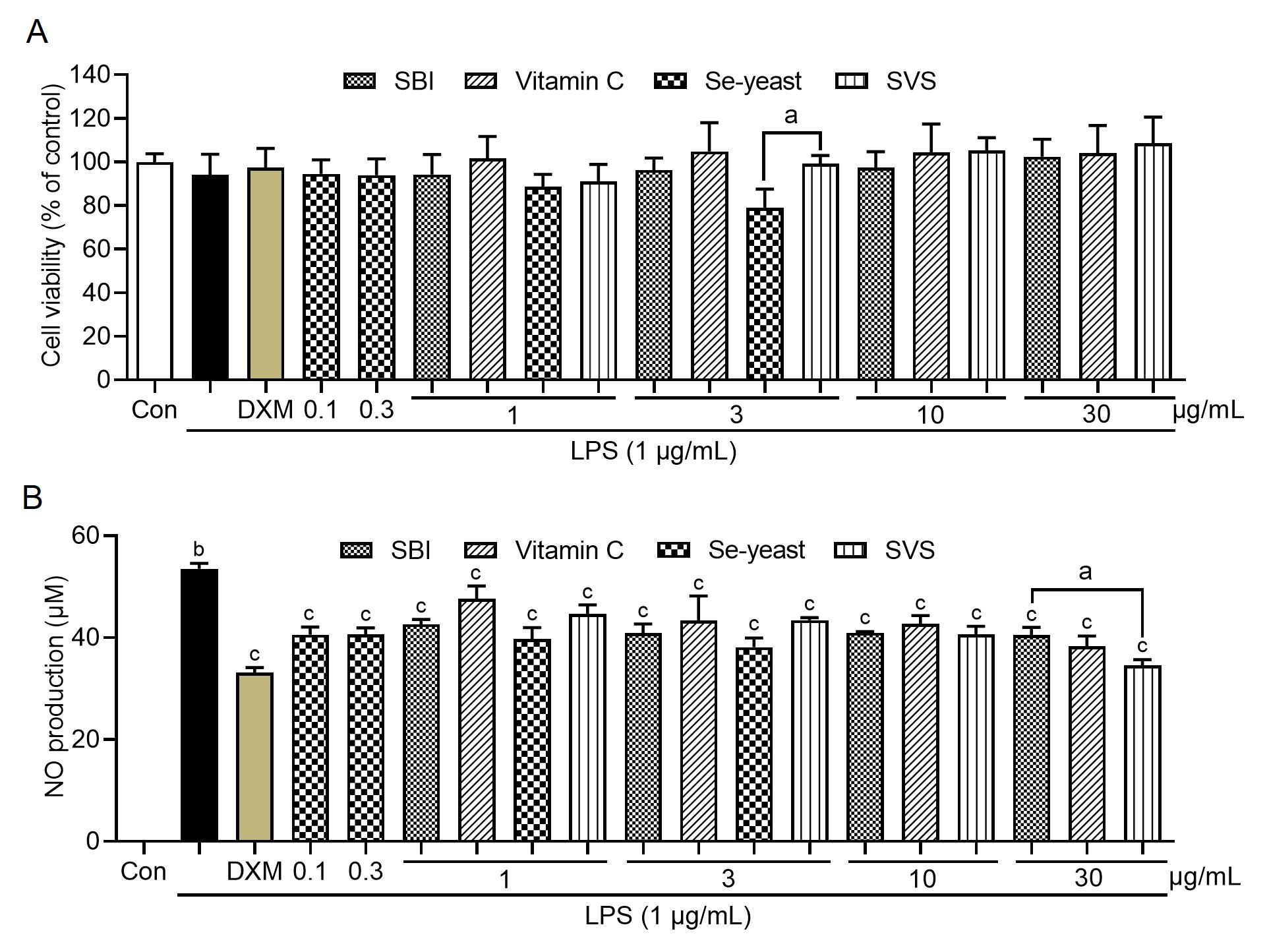

3.3 Effects of SBI, vitamin C, Se-yeast, and SVS on cell viability and NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages

Cell viability was assessed following treatment with the indicated agents at soluble, nontoxic concentrations in the presence of LPS (1 μg/mL). As shown in Figure 3A, no significant cytotoxicity was detected within the concentration range of 0.1–30 μg/mL, as the cell viability remained comparable to that of the control group. However, at 3 μg/mL, Se-yeast significantly reduced cell viability (p < 0.05 vs. the SVS group). Compared with no treatment, LPS stimulation markedly increased NO production (p < 0.05). In contrast, DXM, SBI, vitamin C, Se-yeast, and SVS significantly suppressed LPS-induced NO production (p < 0.05, Figure 3B). Notably, at the same concentration (30 μg/mL), SVS had a significantly greater inhibitory effect on LPS-induced NO production than did SBI (p < 0.05).

Figure 3 Effects of various treatments on LPS-induced changes in cell viability and NO production. (A) Cell viability was measured via an MTT assay and is expressed as a percentage relative to the untreated control. (B) NO production was assessed in culture supernatants via the Griess reaction. The data are shown as the means ± SD (n = 3). a p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between the treatment groups at the same concentration. b p < 0.05 vs. the control group; c p < 0.05 vs. the LPS group; Con, control; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; SBI, serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin protein isolate; SVS, SBI combined with vitamin C and Se-yeast.

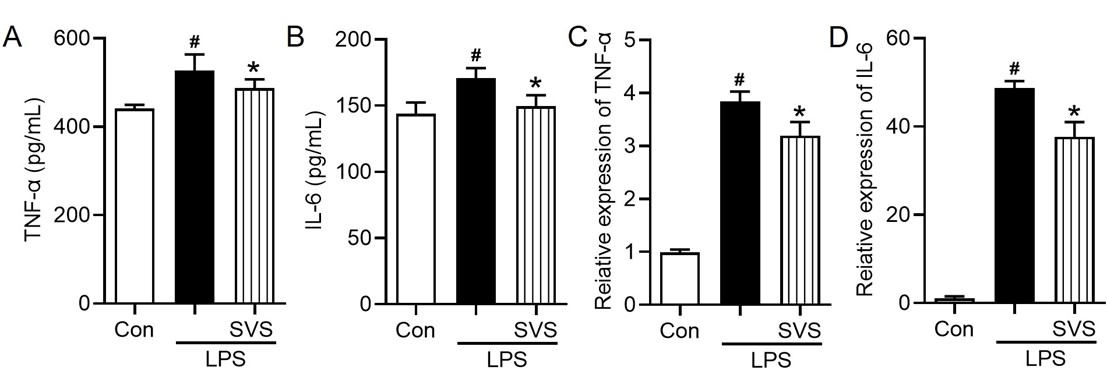

3.4 SVS suppresses LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-6 secretion and mRNA expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages

Compared with the control conditions, LPS stimulation significantly increased TNF-α and IL-6 secretion (p < 0.05; Figure 4A-B). Treatment with SVS (30 μg/mL) significantly attenuated the LPS-induced secretion of both cytokines (p < 0.05 vs. LPS; Figure 4A-B). Consistent with these results, qRT-PCR analysis revealed that, compared with control, LPS significantly upregulated TNF-α and IL-6 mRNA expression (p < 0.05 vs. control; Figure 4C-D), and SVS (30 μg/mL) significantly reduced the transcript level (p < 0.05; Figure 4C-D)

Figure 4 Effects of SVS on TNF-α and IL-6 production in LPS-stimulated macrophages. (A) TNF-α and (B) IL-6 protein levels in culture supernatants; mRNA expression of (C) TNF-α and (D) IL-6. The data are shown as the means ± SD (n = 3). # p < 0.05 vs. the control group; * p < 0.05 vs. the LPS group. Con, control; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; SVS, serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin protein isolate combined with vitamin C and Se-yeast.

3.5 Transcriptomic analysis results

3.5.1 Principal component analysis and differential gene expression

Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed clear separation among the control, LPS, and LPS + SVS groups (Figure 5A), indicating distinct transcriptomic profiles. Differential expression analysis with thresholds of |log2FC| ≥ log2(1.5) and p < 0.05 revealed 2,478 upregulated and 1,693 downregulated genes in the LPS group compared to the control group (Figure 5B). In contrast, the comparison of the LPS + SVS (30 μg/mL) group compared to the LPS group revealed 144 upregulated genes and 170 downregulated genes (Figure 5C). Volcano plots (Figure 5B-C) and a hierarchical clustering heatmap (Figure 5D) further demonstrated that SVS partially reversed LPS-induced transcriptional alterations.

Figure 5 Transcriptomic analysis of differential gene expression in response to LPS and SVS treatment. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) plot showing the separation of the experimental groups. (B) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the LPS vs. control groups. (C) Volcano plot of DEGs in the (LPS + SVS) vs. LPS groups. (D) Heatmap of hierarchical clustering of significant DEGs across groups. Con, control; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; SVS, serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin protein isolate combined with vitamin C and Se-yeast.

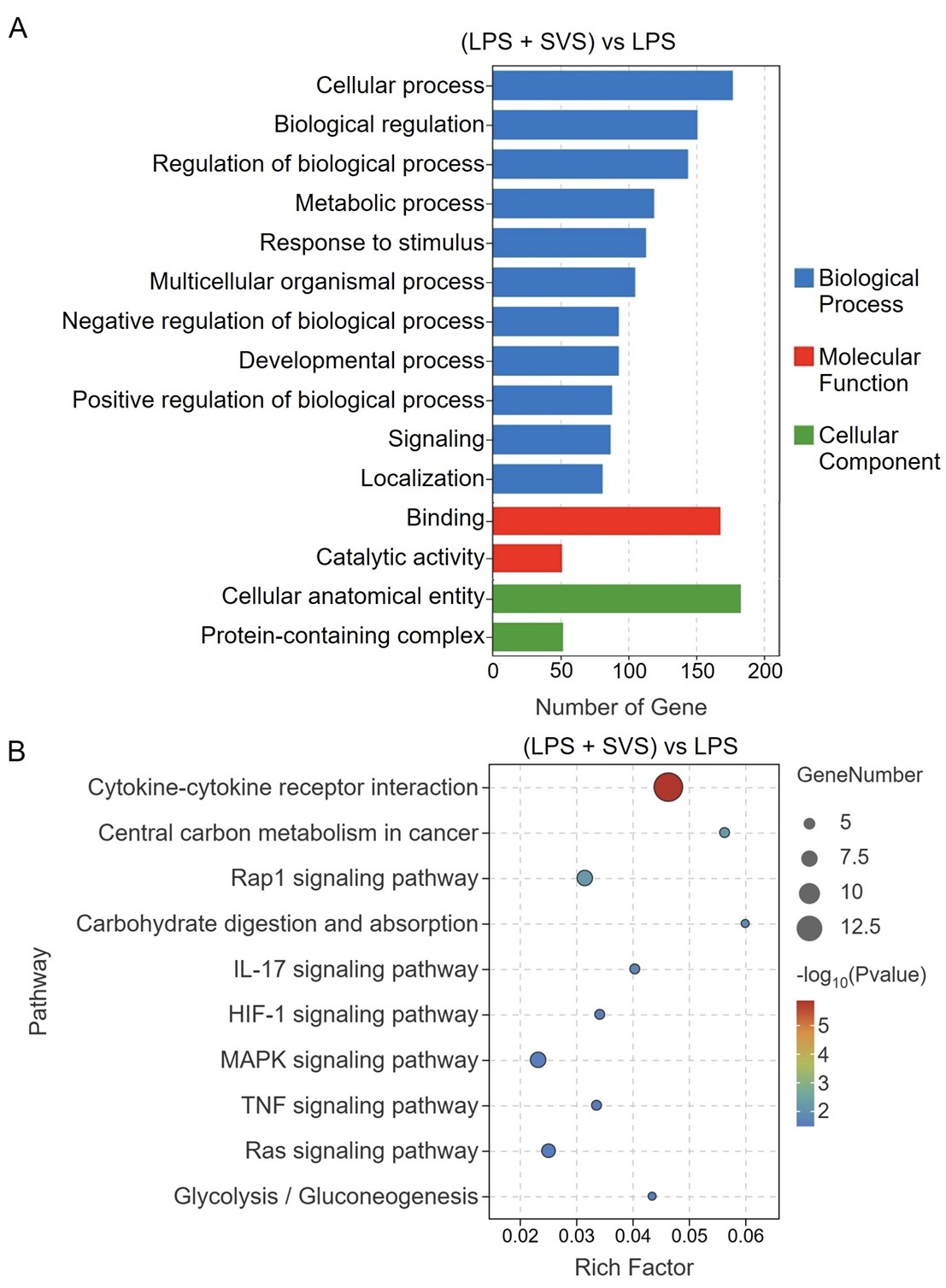

3.5.2 Pathway enrichment analysis

In the comparison between the LPS + SVS and LPS groups, GO enrichment analysis revealed that the DEGs were predominantly associated with biological processes such as cellular process, biological regulation, regulation of biological process, metabolic process, and response to stimulus, whereas binding and catalytic activity were the most enriched molecular functions, and the cellular anatomical entity and protein-containing complex were the major enriched cellular component categories (Figure 6A). KEGG pathway analysis further revealed that these DEGs were significantly enriched in pathways related to immune and inflammatory responses, including the cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, IL-17, and TNF signaling pathways (Figure 6B).

Figure 6 Functional enrichment analysis of DEGs in the (LPS + SVS) vs. LPS comparison. (A) GO enrichment analysis of biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components. (B) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; SVS, serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin protein isolate combined with vitamin C and Se-yeast.

3.5.3 Modulation of cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction genes

In LPS-stimulated cells, SVS treatment significantly modulated the expression of genes associated with the cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction pathway (Figure 7A). Among the 14 key DEGs identified in this pathway (Table 1), 4 were upregulated (e.g., IL7R and CSF2RB2), whereas 10 were downregulated (e.g., CCL22 and INHBA). The most pronounced downregulation was observed for IL34, whereas BMP10 exhibited the strongest upregulation. Notably, the modulated genes included members of the IL-1 family (IL1A, IL1F6, and IL1F9), the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily (TNFRSF9 and TNFSF12), and hematopoietic growth factors (CSF2 and LIF), highlighting the broad immunoregulatory influence of SVS within this signaling network.

Figure 7 Integrated analysis and validation of the cytokine‒cytokine receptor interaction pathway in LPS-stimulated macrophages treated with SVS. (A) Pathway enrichment analysis highlighting upregulated (red) and downregulated (green) DEGs. DEGs further validated by qRT-PCR are marked with blue stars. Validation of the mRNA expression levels of (B) CCL22, (C) IL7R, (D) CSF2RB2, (E) INHBA, (F) TNFRSF9, (G) IL1F6, (H) LIF, and (I) IL1A. The data are presented as the means ± SD (n = 3). # p < 0.05 vs. the control group; * p < 0.05 vs. the LPS group. Con, control; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; SVS, serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin protein isolate combined with vitamin C and Se-yeast.

Table 1 DEGs in the cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction pathway.

| Rank | Gene ID | Gene symbol | log2(FC) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ENSMUSG00000031779 | CCL22 | -1.04 | p < 0.01 |

| 2 | ENSMUSG00000003882 | IL7R | 0.71 | p < 0.01 |

| 3 | ENSMUSG00000071714 | CSF2RB2 | 0.80 | p < 0.01 |

| 4 | ENSMUSG00000041324 | INHBA | -2.61 | p < 0.01 |

| 5 | ENSMUSG00000028965 | TNFRSF9 | -1.08 | p < 0.01 |

| 6 | ENSMUSG00000026984 | IL1F6 | -1.48 | p < 0.01 |

| 7 | ENSMUSG00000034394 | LIF | -1.08 | p < 0.01 |

| 8 | ENSMUSG00000027399 | IL1A | -0.73 | p < 0.01 |

| 9 | ENSMUSG00000023047 | AMHR2 | -0.73 | p < 0.01 |

| 10 | ENSMUSG00000097328 | TNFSF12 | 0.75 | p < 0.01 |

| 11 | ENSMUSG00000044103 | IL1F9 | -0.94 | p < 0.01 |

| 12 | ENSMUSG00000030046 | BMP10 | 2.89 | p < 0.01 |

| 13 | ENSMUSG00000018916 | CSF2 | -1.60 | p = 0.02 |

| 14 | ENSMUSG00000031750 | IL34 | -4.13 | p = 0.03 |

3.6 qRT-PCR validation of key DEGs

To validate the transcriptomic findings, the relative expression levels of the top eight candidate genes—selected on the basis of their lowest P values within the enriched pathways-were assessed via qRT-PCR. Compared with the control conditions, LPS stimulation significantly upregulated the expression of six inflammation- and immunity-related genes, including CCL22, IL7R, TNFRSF9, IL1F6, LIF, and IL1A (Figure 7B-C, F-I). Notably, the expression of four genes-CCL22, TNFRSF9, IL1F6, and LIF-was markedly attenuated in the presence of SVS, indicating a suppressive effect of SVS on LPS-induced proinflammatory responses. Interestingly, SVS further increased the expression of IL7R and CSF2RB2 beyond the levels induced by LPS (Figure 7C-D), suggesting a potential role in modulating receptor-mediated signaling pathways. In contrast, INHBA expression, which was modestly induced by LPS, was reduced following SVS treatment (Figure 7E).

4 Discussion

We demonstrate that the SVS formula-combining SBI, vitamin C, and Se-yeast-exerts context-dependent immunoregulatory and anti-inflammatory effects. In vivo, SVS enhanced ConA-induced splenocyte proliferation and macrophage phagocytosis, whereas in vitro, it attenuated the LPS–driven activation of RAW 264.7 macrophages. Transcriptomic profiling revealed a multitarget mechanism converging on canonical inflammatory pathways. Functionally, SVS reduced NO levels and suppressed both the transcription and secretion of TNF-α and IL-6 (qRT-PCR/ELISA), and it did so more effectively than any individual component did, which is consistent with a synergistic mechanism. These outcomes align with the enrichment of the cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction pathway and the downregulation of MAPK, TNF, and IL-17 signaling, suggesting that SVS is a multipathway anti-inflammatory agent with immunoregulatory activity. The coordinated inhibition of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 by SVS targets key drivers of inflammation. NO modulates inflammatory signaling through both cGMP- and NF-κB-dependent pathways, influencing IκB activity and downstream cytokine expression [24]. Concurrently, TNF-α and IL-6 establish a pathogenic positive feedback loop: TNF-α upregulates IL-6 via NF-κB activation, whereas IL-6 reciprocally enhances TNF-α production. This amplification promotes chemokine release and adhesion molecule expression, which exacerbates tissue injury [25]. Disruption of this axis by SVS mirrors effects previously reported for other natural anti-inflammatory agents in LPS models, such as plantanone C and chlorogenic acid [26,27].

The observed enhanced effects of SVS are likely derived from the complementary mechanisms of its constituents. SBI serves as the core anti-inflammatory component, binding proinflammatory antigens, including LPS, in the gut through immune exclusion and steric hindrance [28]. This reduces immune overstimulation and facilitates barrier repair. Vitamin C contributes to antioxidant activity and epithelial barrier support, reducing lipid peroxidation and suppressing the induction of cytokines, particularly IL-6 [29]. Se-yeast further modulates redox balance and immune-cell function, primarily by attenuating NF-κB-driven transcription and activating PPARγ-mediated anti-inflammatory pathways, with potential implications for IBD [30]. Together, these mechanisms attenuate the reduction in inflammatory initiation at multiple points and establish a cooperative anti-inflammatory network.

This multitarget approach is consistent with principles of network medicine applied to natural-product formulations. Our recent work on Amomum villosum Lour. revealed that network analysis may elucidate synergistic mitigation of inflammation and metabolic dysregulation in alcoholic liver disease via nodes such as ESR1, NR3C1, TNF-α, and IL-6 [31]. Similarly, network–metabolomic integration for Jingling oral liquid demonstrated coordinated regulation of targets (e.g., APP, BDNF, DRD1–DRD4) and pathways (e.g., tyrosine and sphingolipid metabolism) to increase brain dopamine and GABA in ADHD [32]. These precedents support a network-level rationale for SVS. In our setting, selenium and vitamin C likely drive gains in macrophage phagocytosis, whereas SBI predominantly contributes to antigen binding and anti-inflammatory activity—together yielding a more responsive yet restrained immune state.

The transcriptomic data further indicate that SVS not only suppresses isolated cytokines but also reprograms inflammation-related gene networks. KEGG enrichment confirmed significant regulation of the cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction pathway. Although ligand‒receptor binding occurs at the protein level, the expression of these components is governed upstream by inflammatory signaling. Specifically, LPS engagement of TLR4 activates downstream effectors such as NF-κB and MAPK, which drive the secretion of TNF-α and IL-6, upregulate their receptors (e.g., TNFRSF9), and induce chemokines (e.g., CCL22), thereby sustaining a self-amplifying inflammatory loop [33]. SVS-mediated alterations in genes, including CCL22, IL1F6, and TNFRSF9, provide direct evidence that SVS disrupts these LPS-driven transcriptional cascades. Mechanistically, SVS may act at upstream nodes-such as TLR4 signal transduction or kinases, including IKK-thereby limiting the nuclear translocation of transcription factors and attenuating the expression of downstream inflammatory genes. Thus, enrichment of the cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction pathway likely reflects upstream remodeling of the inflammatory transcriptome rather than direct blockade of ligand–receptor binding.

Gene-level validation highlighted several key nodes within this network. CCL22 can exacerbate inflammation and tissue damage (e.g., chondrocyte apoptosis and matrix degradation) and governs immune-cell trafficking (e.g., Treg and dendritic-cell recruitment) via CCR4, thereby shaping the immune microenvironment [34,35]. TNFRSF9 (4-1BB), a costimulatory receptor, activates NF-κB and MAPK signaling upon binding 4-1BBL, regulating T-cell activation, proliferation, and antitumor responses [36]. The SVS-induced downregulation of TNFRSF9 suggests a constraint on T-cell expansion under inflammatory stress. Notably, SVS enhanced ConA-driven T-cell proliferation in vivo but reduced TNFRSF9 expression in LPS-stimulated macrophages in vitro, supporting a model in which SVS augments basal responsiveness but restrains hyperinflammatory proliferation. IL1F6 (IL-36α), an IL-1 family cytokine that promotes dendritic cell activation, Th17 polarization, and proinflammatory cytokine production via IL-36R [37], is also inhibited by SVS; this may reduce IL-6 output and help restore immune balance, such as the Th17/Treg ratio. In addition to affecting the TNF and MAPK pathways, SVS influences Rap1 signaling-implicated in leukocyte adhesion and migration-and modulates glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and central carbon metabolism, which is consistent with the partial restoration of immunometabolic homeostasis [38]. This concept resonates with our recent demonstration that ginkgolide B protects cardiomyocytes by preserving mitochondrial function through VDAC1 [39], highlighting mitochondrial and metabolic regulation as recurring cytoprotective themes that may also underlie SVS activity.

These mechanisms hold significant translational relevance. The clinical success of pathway-targeted therapies for arthritis and enteritis underscores the potential utility of the SVS-associated transcriptomic signature [40,41]. Collectively, our findings establish that the SVS formula exhibits a unique bidirectional immunomodulatory profile. To our knowledge, this study provides the first in vivo evidence that combined SBI-vitamin C-Se-yeast intervention enhances basal immune functions—including lymphocyte proliferation and macrophage phagocytosis-while simultaneously attenuating excessive inflammation. Such bidirectional regulation may be particularly advantageous in chronic inflammatory conditions accompanied by immune insufficiency, such as age-associated inflammation or postinfectious syndromes. Furthermore, the absence of detectable cytotoxicity at therapeutically effective concentrations represents a key advantage over conventional anti-inflammatory agents, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and glucocorticoids, which are often limited by adverse effects, including gastric mucosal injury mediated by cyclooxygenase inhibition and impaired prostaglandin synthesis [42].

This study has several limitations. The in vitro validation was primarily conducted in a macrophage cell line, and the efficacy of SVS in more complex systems involving immune cell crosstalk remains to be investigated. Furthermore, while our study included valuable comparisons with individual components (both in vivo and in vitro), it did not incorporate a control group consisting of a physical mixture of all three individual components at the same ratios as in the SVS formula. The inclusion of such a group in future studies would be necessary to rigorously distinguish between synergistic and merely additive effects. Consequently, future work should evaluate SVS in established inflammatory disease models (e.g., DSS-induced colitis), and the inclusion of this full-component mixture control is essential to fully elucidate the nature of the component interactions. If supported by robust preclinical data, early-phase clinical studies could then clarify the translational potential of SVS.

5 Conclusion

SVS—a composite of SBI, vitamin C, and Se-yeast-shows context-dependent immunomodulation: it augments ConA-induced splenocyte proliferation and macrophage phagocytosis in vivo while suppressing LPS-driven inflammation in vitro. This bidirectional profile arises from multiple mechanisms, including coordinated suppression of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6; reprogramming of cytokine–receptor networks; and downregulation of TNF/MAPK/IL-17 signaling with concomitant effects on immunometabolic pathways (e.g., HIF-1/glycolysis). These enhanced effects, achieved without detectable cytotoxicity at effective doses, position SVS as a safe, multimechanistic functional food candidate for mitigating chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation.

Back Matter

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author of this article, Guozhen Cui, is a member of the editorial office of this journal. All procedures during the editorial review process were conducted strictly in accordance with the journal's policies, and the author was not involved in handling any part of the process.

Author Contributions

Z.W.: Methodology, Software, Validation, Data curation, Writing–original draft, Formal analysis. L.Z.: Validation, Data curation. H.Q.: Validation, Data curation. Y.Z.: Writing–original draft. Y.L.: Data curation, Investigation. W.L.: Data curation, Visualization. Y.C.: Data curation, Investigation. Y.H.: Investigation. G.C.: Conceptualization, Writing–review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All the experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Welfare Ethics Committee of Zunyi Medical University (No: ZHSC-2-[2024]041), and all the methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the Guizhou Province Science and Technology Program (Grant No. Qiankehe support [2023] General 071) and the Innovation Team Project by the Department of Education of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2024KCXTD005).

Availability of Data and Materials

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://ojs.exploverpub.com/index .php/jecacm/article/view/318/sup. Supplementary Table S1: Primer sequences used for qRT-PCR.

References

- Bonaguro L, Schulte-Schrepping J, Ulas T, et al. A guide to systems-level immunomics. Nature Immunology 2022; 23(10): 1412-1423.

- Dikiy S, Rudensky AY. Principles of regulatory T cell function. Immunity 2023; 56(2): 240-255.

- Chazaud B. Inflammation and Skeletal Muscle Regeneration: Leave It to the Macrophages! Trends in Immunology 2020; 41(6): 481-492.

- Collaborators GDaI. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 2020; 396(10258): 1204-1222.

- Cheong JG, Ravishankar A, Sharma S, et al. Epigenetic memory of coronavirus infection in innate immune cells and their progenitors. Cell 2023; 186(18): 3882-3902.

- Lim J, Puan KJ, Wang LW, et al. Data-Driven Analysis of COVID-19 Reveals Persistent Immune Abnormalities in Convalescent Severe Individuals. Frontiers in Immunology 2021; 12: 710217.

- Bindu S, Mazumder S, Bandyopadhyay U. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and organ damage: A current perspective. Biochemical Pharmacology 2020; 180: 114147.

- Van den Abbeele P, Kunkler CN, Poppe J, et al. Serum-Derived Bovine Immunoglobulin Promotes Barrier Integrity and Lowers Inflammation for 24 Human Adults Ex Vivo. Nutrients 2024; 16(11): 1585.

- Utay NS, Asmuth DM, Gharakhanian S, et al. Potential use of serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin/protein isolate for the management of COVID-19. Drug Development Research 2021; 82(7): 873-879.

- Hazan S, Bao G, Vidal A, et al. Gut Microbiome Alterations Following Oral Serum-Derived Bovine Immunoglobulin Administration in the Management of Dysbiosis. Cureus 2024; 16(12): e75884.

- Bateman E, Weaver E, Klein G, et al. Serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin/protein isolate in the alleviation of chemotherapy-induced mucositis. Supportive Care in Cancer 2016; 24(1): 377-385.

- Shaw AL, Tomanelli A, Bradshaw TP, et al. Impact of serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin/protein isolate therapy on irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease: a survey of patient perspective. Patient Prefer Adherence 2017; 11: 1001-1007.

- Valentin N, Camilleri M, Carlson P, et al. Potential mechanisms of effects of serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin/protein isolate therapy in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Physiological Reports 2017; 5(5): e13170.

- Arikapudi S, Rashid S, Al Almomani LA, et al. Serum Bovine Immunoglobulin for Chemotherapy-Induced Gastrointestinal Mucositis. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care 2018; 35(5): 814-817.

- Stotts MJ, Cheung A, Hammami MB, et al. Evaluation of Serum-Derived Bovine Immunoglobulin Protein Isolate in Subjects With Decompensated Cirrhosis With Ascites. Cureus 2021; 13(6): e15403.

- Bedhiafi T, Inchakalody VP, Fernandes Q, et al. The potential role of vitamin C in empowering cancer immunotherapy. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022; 146: 112553.

- Nowak D. Vitamin C in Human Health and Disease. Nutrients 2021; 13(5): 1595.

- Ferrari L, Cattaneo D, Abbate R, et al. Advances in selenium supplementation: From selenium-enriched yeast to potential selenium-enriched insects, and selenium nanoparticles. Animal Nutrition 2023; 14: 193-203.

- Yang J, Yang H. Recent development in Se-enriched yeast, lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2023; 63(3): 411-425.

- Wu Z, Luo W, Kuang S, et al. Integrated gut microbiota and serum metabolomic analysis to investigate the mechanism of the immune-enhancing effect of SVS formula in mice. Journal of Functional Foods 2024; 122: 106468.

- Wang Y, Zhang Y, He Y, et al. GGV formula attenuates CCl(4)-induced hepatic injury in mice by modulating the gut microbiota and metabolites. Frontiers in Nutrition 2025; 12: 1564177.

- Ren A, Wu T, Wang Y, et al. Integrating animal experiments, mass spectrometry and network-based approach to reveal the sleep-improving effects of Ziziphi Spinosae Semen and gamma-aminobutyric acid mixture. Chinese Medicine 2023; 18(1): 99.

- Qin T, Ali K, Wang Y, et al. Global transcriptome and coexpression network analyses reveal cultivar-specific molecular signatures associated with different rooting depth responses to drought stress in potato. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022; 13: 1007866.

- Facchin BM, Dos Reis GO, Vieira GN, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers on an LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cell model: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflammation Research 2022; 71(7-8): 741-758.

- Tylutka A, Walas L, Zembron-Lacny A. Level of IL-6, TNF, and IL-1beta and age-related diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Immunology 2024; 15: 1330386.

- Gu T, Zhang Z, Liu J, et al. Chlorogenic Acid Alleviates LPS-Induced Inflammation and Oxidative Stress by Modulating CD36/AMPK/PGC-1alpha in RAW264.7 Macrophages. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023; 24(17): 13516.

- Fang Y, Yang L, He J. Plantanone C attenuates LPS-stimulated inflammation by inhibiting NF-kappaB/iNOS/COX-2/MAPKs/Akt pathways in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021; 143: 112104.

- Detzel CJ, Horgan A, Henderson AL, et al. Bovine immunoglobulin/protein isolate binds pro-inflammatory bacterial compounds and prevents immune activation in an intestinal co-culture model. PLoS ONE 2015; 10(4): e0120278.

- Righi NC, Schuch FB, De Nardi AT, et al. Effects of vitamin C on oxidative stress, inflammation, muscle soreness, and strength following acute exercise: meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials. European Journal of Nutrition 2020; 59(7): 2827-2839.

- Nettleford SK, Prabhu KS. Selenium and Selenoproteins in Gut Inflammation-A Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2018; 7(3): 36.

- Wei J, Wang S, Huang J, et al. Network medicine‐based analysis of the hepatoprotective effects of Amomum villosum Lour. on alcoholic liver disease in rats. Food Science & Nutrition 2024; 00: 1–15.

- Luo W, Zhang S, Li Y, et al. Integrated metabolomic analysis and network medicine to investigate the mechanisms of Jingling oral liquid in treating ADHD. Clinical Traditional Medicine and Pharmacology 2025: 200214.

- Qiao H, Ren H, Liu Q, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Rehmannia glutinosa polysaccharide on LPS-induced acute liver injury in mice and related underlying mechanisms. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2025; 351: 120099.

- Xu H, Lin S, Huang H. Involvement of increased expression of chemokine C-C motif chemokine 22 (CCL22)/CC chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4) in the inflammatory injury and cartilage degradation of chondrocytes. Cytotechnology 2021; 73(5): 715-726.

- Baer C, Kimura S, Rana MS, et al. CCL22 mutations drive natural killer cell lymphoproliferative disease by deregulating microenvironmental crosstalk. Nature Genetics 2022; 54(5): 637-648.

- Fröhlich A, Loick S, Bawden EG, et al. Comprehensive analysis of tumor necrosis factor receptor TNFRSF9 (4-1BB) DNA methylation with regard to molecular and clinicopathological features, immune infiltrates, and response prediction to immunotherapy in melanoma. EBioMedicine 2020; 52: 102647.

- Blumberg H, Dinh H, Trueblood ES, et al. Opposing activities of two novel members of the IL-1 ligand family regulate skin inflammation. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2007; 204(11): 2603-2614.

- Zhang R, Xue T, Shao A, et al. Bclaf1 regulates c-FLIP expression and protects cells from TNF-induced apoptosis and tissue injury. EMBO Reports 2022; 23(1): e52702.

- Wu T, Li D, Chen Q, et al. Identification of VDAC1 as a cardioprotective target of Ginkgolide B. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2025; 406: 111358.

- Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, et al. Ustekinumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Crohn's Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2016; 375(20): 1946-1960.

- Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. New England Journal of Medicine 2013; 369(8): 699-710.

- Vakil N. Peptic Ulcer Disease: A Review. The Journal of the American Medical Association 2024; 332(21): 1832-1842.